Jason Tseng

What We Talk About When We Talk About Transforming the Field

Posted by Aug 07, 2015 0 comments

Jason Tseng

“To fundamentally transform the field in order to meet a fundamentally changing nation and time, we need to fundamentally change who is in the field ”

This was the prompt I was given, earlier this year, when I was asked to speak at the Americans for the Arts Convention. It so happens that I spend a lot of time thinking about transforming the arts and culture field; on the account of the fact that I work for Fractured Atlas, a nonprofit technology organization that helps artists with the business side of the creative work, where transforming the status quo of the field is part and parcel of everything that we do.

But the kind of transformation to which this question refers — one centered around issues of diversity and cultural equity — especially resonates with me because I come to this work specifically through a social justice lens. Many conversations on the issue diversity and the arts are good at identifying the symptoms, but fail to frame their solutions to solve a problem that is systemic, entrenched, and ubiquitous.

What we mean when we say “The Field?”

Before we can transform the field, we first have to understand what it is:

- It’s not just the traditional disciplines (e.g. theatre, dance, music, visual art, literature, etc.): “the Arts” sector frequently separates itself from “applied creativity” like product design, fashion, graphic design, video games, etc. But in reality, it’s much more productive and realistic to consider all creative pursuits as a collective whole.

- It’s not just non-profit institutions: too often we only talk about the arts through the lens of non-profit institutions, but it’s important to recognize that a large portion of “the field” is actually comprised of individual artists, sponsored projects, for profit art makers, folk traditions, and more.

- It’s not a monolithic entity: in spite of our best efforts, the arts are not one unified force, which means there isn’t a single person or force calling the shots.

- It is a system: like all social systems, it is created and recreated from innumerable tiny hyper-local choices and actions. This means that the social forces that maintain the status quo of the field often play out at the micro level without any intentionality or malice, but which, when magnified across an entire sector, have macro consequences.

- It does not operate in a vacuum: our Arts and Culture system, like other social systems, is enmeshed with our broader society and economy.

So, if we understand that we live in a society that is racist, classist, sexist, heterosexist, ableist, colonialist, or otherwise hegemonically oppressive, as the prompt seems to indicate; then it would fall to reason that our Arts and culture system will instinctively reproduce the same oppression of the society with which it is entangled.

Where are we now?

To many, this statement is an obvious one. But I have time and time again been confronted by people who refuse to believe that our field has a problem with cultural equity. The assertion becomes that any symptoms of inequity are due to forces outside of the control of the arts, and therefor not our responsibility, or at the very least do not take precedence over “artistic excellence.”

I’ll let the numbers speak for themselves:

1. We know that our society suffers from incredible wealth inequality.

In 2015, researchers found that the richest 3% of Americans owned 55% of all wealth in the United States, with the bottom half of Americans owning less than 1% of U.S. financial assets.

Thanks to the research of Holly Sidford, we know that the nonprofit arts sector is a near mirror of this, with the largest 3% of arts organizations (by budget size) received roughly 60% of all arts and culture contributed income with the bottom half of the nonprofit arts field only receiving 5% of contributed income.

2. Hegemonic oppression worsens the resource gap.

If we look broadly at our society, we see how White households’ median wealth is about ten times larger than that of Latin@ households, and about 13 times larger than that of Black households. In addition, while the gender pay gap is a well known phenomenon, research shows it’s even worse for women of color.

Again, we see this reproduced in the arts — Sidford’s research found that only 10% of Arts and Culture grant dollars were classified as benefiting marginalized communities, while the U.S. is roughly 40% people of color. This disparity is often exacerbated at the local level. Consider California — a report found that just 9% of in-state arts grant dollars went to benefit people of color, who represent about 60% of Californians.

3. This oppression-exacerbated resource gap inhibits our ability to participate in society.

The results are staggering in business, and also in the arts — only 5% of US art museum directors are people of color, 86% of local arts agency employees are White, almost 8 of 10 roles on NYC stages were performed by White actors (where only 1 in 3 New Yorkers are Non-Hispanic White), and only 4% of U.S. Orchestra players are Black or Latin. Hegemonic cultural oppression fundamentally impacts who shows up, who participates, and who leads in our field.

How did we get here?

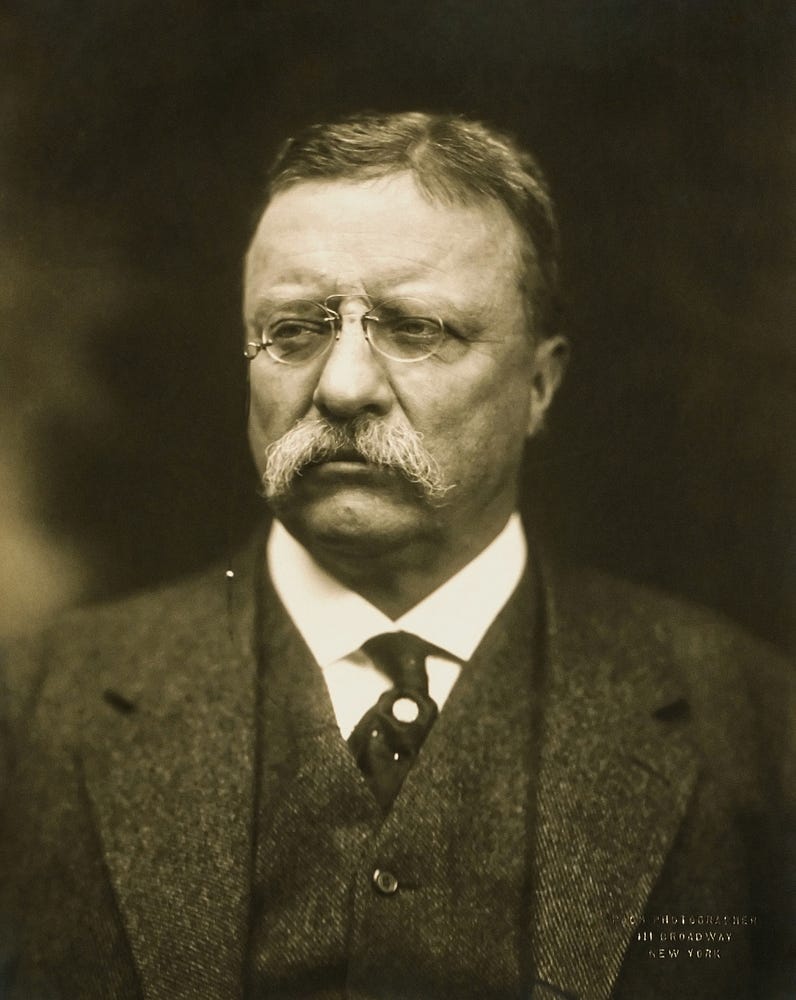

“Of all forms of tyranny the least attractive and the most vulgar is the tyranny of mere wealth, the tyranny of plutocracy.” — Theodore Roosevelt

During the Progressive Era, Theodore Roosevelt staunchly opposed the reach and power of the wealthy, in spite of himself hailing from one of America’s wealthiest families. Roosevelt actively used the government to curb the influence of the industrial capitalists, and to protect public assets from the private sector. One of his greatest and most beloved accomplishments was the establishment of the National Parks system, which shielded tens of thousands of acres of public land from private interest.

It was during this time period when the first major philanthropic institutions were created by America’s wealthiest. Roosevelt vehemently opposed the creation of these institutions, saying of them,

“No amount of charity in spending such fortunes can compensate in any way for the misconduct in acquiring them.”

This system of inequity we have inherited didn’t spring up suddenly or by accident, but rather finds its roots in the expansion of influence by wealthy industrialists via the philanthropic institutions they controlled.

The resources and power in the arts are concentrated in an incredibly small number of gatekeepers, who disproportionately represent the interests and demographics of the hegemonic class (read: white, wealthy, able-bodied, heterosexual, etc.). As the government has ceded more responsibility to the social sector (and by extension, philanthropy), the influence of these gatekeepers has only increased.

Where are we headed?

“The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” -Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Many believe that our society is inherently progressive and that our society grows more equitable over time.

But… does it?

- According to Nate Silver’s Blog fivethirtyeight, the more diverse our cities become, the more segregated they are.

- The Washington Post found that millennials are just as racist as their forebears.

- Oxfam predicts that by 2016, the world’s richest 1% will own more wealth than the rest of the global population.

The metrics point to us living in a world that is more segregated, divisive, and unequal than ever before.

What hope do we have?

What hope do we have?

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” — Audre Lorde

The legendary black, lesbian, feminist and civil rights activist and writer Audre Lorde wrote frequently on the subject of dismantling oppressive systems. She particularly believed that our liberation will not be found in the status quo.

Luckily, we live at an unprecedented moment in history where the rate of innovation is rapidly accelerating and disrupting much of the status quo, as we know it.

The economist Joseph Schumpeter called innovation, creative destruction: “the process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one.”

Disruptive technology has allowed for the rise of disintermediation — open media platforms and new trends like crowdfunding are making it easier for artists to find connect, engage, and cultivate their fans.

At the same time, we’re witnessing a falling barrier of entry in terms of start-up costs for new creative projects. Economist and venture capitalist Bill Janeway describes how the combination of open source software and cloud-based web services is causing the cost of launching a new service to asymptotically approach zero.

Part of what Fractured Atlas does is help reduce those startup costs in the arts so that more creators can enter the market. But more than that, we are trying to move the field from an institution-centered system to a person-centered system.

Unfortunately, fixing the market is not enough. Even if we reduce the cost of entry to zero and somehow distribute all the arts and culture funds equitably across the field; we will not solve the inequity problem in the arts until we address hegemonic cultural oppression.

However, this is where the arts in its content can be a major player in resisting and dismantling the hegemonic beliefs and stereotypes which oppress marginalized communities. Earlier this year, Norman Lear gave a great speech on the role of using the arts to combat racism, sexism, homophobia, and to further progressive politics at Americans for the Arts' 28th Annual Nancy Hanks Lecture on Arts and Public Policy.

But before we can begin to use the arts as a tool for liberation, we must first wrestle with the disease within our own ranks. We must admit our complicity with this oppressive system, and then actively undo the injustice we have perpetuated. We must understand that while all oppressions are not the same, they are linked to each other — and that only through solidarity will we truly transform the field that we love so dearly.

This blog was originally published on Medium.com by Jason Tseng on July 29.